Special Topics:

The 5-E Process of Solution-Focused Intervention in Schools

The following text is adapted from two primary sources:

Murphy, J. J. (1994). Working with what works: A solution-focused approach to school

behavior problems. The School Counselor, 42, 59-65.

Murphy, J. J. (1999). Common factors of school-based change. M.A. Hubble, S. D., Miller, B. L. Duncan (Eds.), The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy. Washington,DC: American Psychological Association. (pp. 361-386).

In dealing with a school problem involving an individual student or an entire school staff, efforts usually focus on reducing or eliminating the problem. Assessment clarifies various features of the problem such as its history and presumed causes. Intervention is practitioner-directed. Strategies are prescribed to clients on the basis of the expert’s chosen treatment model. These methods imply that there is something defective about the client or client system, and that the problem will be resolved only when the deficits are corrected.

The deficit-based perspective is strongly embedded in a range of human service contexts including schools. However, this perspective flies in the face of what works to promote change. Empirical findings on common factors in psychotherapy (Garfield, 1994; Lambert, 1992) and school-based intervention (Carlson et al., 1992; Conoley et al., 1992; Shectman, 1993; Witt & Elliott, 1985) indicate that change is enhanced when practitioners persistently recognize and utilize the client’s strengths, beliefs, resources, experiences, ideas, and hope throughout the change process. Respect for the client’s contribution to change is paramount to effective outcomes.

In contrast to deficit-based approaches, the 5-E Method (Murphy, 1994) adopts a competency orientation grounded in the following common factors notions:

· change is enhanced when people are viewed as resourceful and capable of improving their lives,

· cooperation and collaboration promote change,

· change efforts that focus on future possibilities instead of past problems promote hope and solutions,

· change is enhanced when practitioners techniques are flexibly selected to fit the client instead of expecting the client to conform to the invariant and favorite techniques of the practitioner.

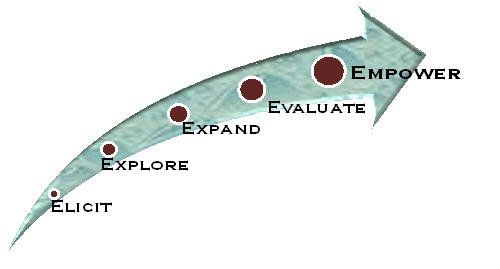

Description of the 5-E Process

The 5-E process was originally applied to school behavior problems (Murphy, 1994), but is expanded here to include any type of school-based change. The 5-E process is a systematic approach to using exceptions to problems and other client resources in order to bring about change. Exceptions are nonproblem aspects of the client and his or her circumstances, including: (a) times and situations in which the problem is absent or less noticeable (e.g., in the case of a student referred for a behavior problem, the classes or times at school during which the student is well-behaved) and (b) strengths and resources of the client which are antithetical to the problem or that could be applied toward the goal of change (e.g., in the case of a school staff that wishes to improve its image in the community, the staff members who are already well-respected in the community). The 5-E process involves five steps or tasks which are implemented within a collaborative framework. Collaboration is ensured when practitioners accept, acknowledge, and accommodate the unique ideas and resources of the people expected to implement a change (Murphy & Duncan, 1997).

Step 1: Eliciting. Once practitioners obtain a clear sense of the client’s goal at the outset of intervention, they can empower “client factors” by identifying exceptions to the problem and other client resources. This is not as easy as it sounds. Students and others who are involved in a school problem often view it as constant and unchanging. As de Shazer (1991, p. 58) observes, “times when the complaint is absent are dismissed as trivial by the client or even remain completely unseen, hidden from the client’s view.”

Other resources include the client’s hobbies, talents, interests, family, friends, and ideas about potential solutions. Similar to exceptions, these resources often go unnoticed in the face of serious school problems. For example, it is easy to overlook a student’s strong interests in music when responding to an urgent request to alter the student’s undesirable classroom behavior. However, the student’s musical interest might be utilized in an important and powerful way in addressing the classroom problem. Since students and others typically do not volunteer information regarding exceptions and other important resources, it is necessary to elicit such information with the following types of questions:

· Of all your classes, which one is the most tolerable? Which class do you do best in?

· When is this problem absent or less noticeable?

· What do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

· How might someone finish this sentence about you: “This person is really good at...?

· How have you managed to keep things from getting worse?

· Of all the things you’ve already tried in dealing with this, which strategy worked best, if only just a little better than the others?

· How have you handled similar situations in the past?

· Are you or your family connected with any places or groups that might help you with this problem?

· If you were the counselor/consultant in this situation, what would you say to someone who is struggling with this type of situation?

Students, teachers, parents, and other clients can provide essential information and ideas toward intervention goals if they are asked. Problem solving is impeded when clients are viewed merely as “keepers” of the problem with little or nothing to offer toward its solution (Murphy, 1997). Eliciting exceptions and other resources serves not only to empower client factors, but also mobilizes relationship and expectancy factors. Asking about the clients’ previous successes, coping strategies, social supports, and other competencies establishes a collaborative relationship and sets an optimistic tone of hope and expectancy.

Step 2: Exploring. Once an exception or other resource is discovered, practitioners can explore it by inquiring about related circumstances. The same kinds of questions used to clarify problem-related factors are helpful in clarifying information related to exceptions and other resources. For example, a student who misbehaves frequently in every class except math class might be asked the following questions to clarify this exception:

· What is different about your math class than your other classes? What else?

· What is different about your math teacher than your other teachers? What else?

· Where do you sit in math class?

· How would you rate your interest in math as compared to your other classes?

· How do you resist the urge to mess around more in math class?

Consider the school principal who complained that it was “like pulling teeth” to get help from the faculty. Following the discovery of an exception to the problem in which several faculty members responded more favorably to one particular request for help, she was asked the following questions:

· What were you asking for in this case?

· How did you communicate this request?

· What else was different about this request than most of the other requests you have made of faculty members?

The exception was more fully explored with similar questions, and it was discovered that the “exceptional” request was different from most others in the following ways: (a) it was presented “in person” instead of by memorandum; (b) to small groups of faculty members instead of to the entire faculty; and (c) as part of an overall school goal, not an isolated, discrete task.

Other client resources can be explored in similar ways. For example, in consulting with a high school staff seeking to revise its curriculum, the consultant can inquire about the details and circumstances of other school-wide changes that have been successfully implemented.

Step 3: Expanding. This is the heart of the 5-E process in which clients are encouraged to expand exceptions and other resources in ways that impact intervention goals. Consider the student who behaves better in history than any other class. On discovering that history was the only class in which the student sat close to the teacher and the chalkboard, the counselor encourages the student to sit closer to the teacher in another class or two. Improvements in school problems frequently result from expanding “what works” in one context to another, then another, and so on.

In addition to expanding successes and resources to other situations, people can be encouraged to “do the exception” more frequently. Recall the principal who discovered important distinctions between circumstances related to successful and unsuccessful requests for faculty assistance. In this case, she decided to make the exception the rule in communicating future requests to faculty. The results were quite favorable.

As another example, consider a case of a ninth grade biology teacher requesting help in managing the behavior of his entire class. When asked about times or activities when things went a little smoother in class, he reported fewer behavior problems (the exception) during small group activities and experiments (the exception context). I suggested that he consider doing more activities and experiments in class, providing that course objectives could still be met while doing so. When I saw the teacher the next month, he commented that the class was much better and that he was doing some type of special activity almost every day. As we talked, it became evident that he had modified my suggestion in two creative ways. First, whenever possible, he scheduled group activities and experiments during the last half of the class because students’ behavior was usually worse during the latter portion of class. Second, he offered certain “special activities” as rewards contingent upon acceptable classroom behavior during the entire week. That is, he modified the intervention to make it more acceptable. The collaborative aspect of the 5-E approach encourages people to adapt interventions to their own unique style and circumstances. They know better than we do what will work (and not work) for them.

Step 4: Evaluating. In traditional intervention approaches, effectiveness is evaluated by practitioner-selected measures. Client judgments, if solicited at all, play a minor role in gauging the success of intervention. In contrast, the 5-E process regards client judgments as central in evaluating interventions. The following evaluation methods are responsive to client-directed nature of this approach as well as the time constraints and other practical realities of practitioners.

Scaling is a quick way to assess progress on an ongoing basis. People can be asked variations of the following scaling question on a regular basis throughout the intervention process: “On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being ‘the worst’ and 10 ‘the best’, how would you rate the problem during the past week?” Refer to Kowalski and Kral (1989) for additional discussion of scaling techniques.

Paper-and-pencil methods can also be employed to assess change by asking people to complete rating scales, checklists, inventories, or questionnaires. If available rating scales do not sufficiently address the goals of change, practitioners can design simple checklists and forms that address the goals of intervention.

Another method of evaluating the effectiveness of intervention is by examining data from permanent products such as report cards, test scores, and discipline records. For example, comparison of a school district’s overall achievement scores and discipline records before, during, and following a staff development project could be used to evaluate the project’s effectiveness.

Step 5: Empowering. When desired changes occur, the emphasis shifts toward empowering these changes and helping people maintain them. The maintenance of treatment gains has been extensively covered in the literature (Lambert & Bergin, 1994; Nicholson & Berman, 1983; Stokes & Baer, 1977), and this section highlights those strategies that are particularly compatible with the notion of utilizing client resources. The 5-E Process “begins with the end in mind” by routinely employing maintenance strategies throughout the change process.

Collaborating with clients throughout the change process is one of the surest methods for promoting ownership and maintenance of desired changes. One way to do this is by “offering” suggestions instead of telling people what to do. People who perceive their role in the change process as active and important are more likely to continue applying interventions on their own (Reinking et al., 1978).

Another way to empower positive changes is to blame the client for such changes (Kral, 1986). This strategy is based on the notion that people are more likely to maintain improvements when they attribute the result to something they did, and can do again in the future (Murphy, 1997). The following questions help people clarify their role and contribution to successful changes:

· How did you make it through math class for a whole week without getting kicked out?

· What are you doing differently now to create this type of positive learning atmosphere in your class?

· How did you manage to get your daughter to school on time for the past three days?

· What does this tell you about yourself? What do you think this tells your parents and teachers about you?

· How did you get this to happen? What did you do differently?

· How did you get faculty to volunteer more for projects?

Practitioners can also encourage people to clarify their plans for maintaining progress by asking variations of the question, “How are you going to maintain these changes?” In addition to helping people clarify their intentions to maintain progress, the following questions convey the practitioner’s expectation and confidence in their ability to do so:

· Do you plan to continue these changes? Why is it important for you to do so?

· What can you do to continue the progress you have made so far?

· How are you going to stick with this plan in the future?

These questions apply to any context of school-based change including counseling, teaching, consultation, and organizational development. In terms of common factors, these questions convey a positive expectancy regarding clients’ ability to successfully maintain changes. Next, the 5-E process is illustrated by way of a short case example involving a group of high school students.

Illustration of the 5-E Process: The Test Anxiety Group

Five female students in grades 10 and 11 were referred to the school psychologist by their counselor for test anxiety problems. They participated in six group counseling sessions in which the strategy of utilizing exceptions and other resources was combined with educational and skill-building activities in the areas of study skills, test-taking, and relaxation.

During the first meeting, students completed some basic information forms and responded to questions about what they hoped to gain from the group. Their goals included improved test performance, better study habits, and less worry and tension before important tests. In the beginning of the second session, each student was asked to think of one or two recent testing situations in which they studied more effectively, were a little more relaxed than usual, or received a higher grade. This question was designed to elicit exceptions, and was directly tied to the stated goals of the group. After the students listed their exceptions, they were explored through the following types of questions:

· What subject area was the test in? What was different about this test compared to other tests?

· What was different about the way you prepared for the test?

· What did you do differently right before the test? During the test?

· How did you study for the test? What was different about the way you studied?

· How did you manage to relax more?

Students expressed appreciation for the opportunity to discuss what they were already doing to help themselves. One student commented, “I thought I was doing everything wrong.” The students were urged to continue paying attention to those times and circumstances in which they studied more effectively, performed better, and were more relaxed during a test. They were also encouraged to expand on the successes and coping resources during the following week. For example, a student who said she relaxed more effectively during a math test by taking a few 10-second breaks was invited to take similar breaks during her upcoming history test.

In addition to the educational material presented throughout the next four sessions, the practitioner continued exploring exceptions, resources, and related circumstances. Educational and skill-building material on test-taking, relaxing, and studying was integrated with student-generated ideas and strategies.

The collaborative style of group leadership enhanced the acceptability of the counselor’s suggestions and to increase students’ ownership of the ideas and strategies presented during the group. When students reported improvements, these changes were empowered by asking them how they managed to bring them about and how they intended to maintain them. Students developed several creative strategies for maintaining desired changes. For example, one student carried a small card containing test-taking tips that she could conveniently review immediately prior to a test. Another student taught her younger sister many of the study and test-taking strategies covered by the group, adding that this greatly improved her own understanding and application of these strategies.

In terms of evaluating the effectiveness of the group, it was agreed upon during the first meeting that grades were the best indicators of progress. Four of the five students increased their overall grade point average, and all five students reported improvements in test-taking skills on a self-report questionnaire. The comments that students made following the group's termination were indicative of the collaborative and empowering nature of the 5-E process:

Although space limitations preclude other examples of the 5-E process, this approach is applicable to any type of school-based change ranging from behavior problems of an individual student to organizational changes involving an entire school or school district. Additional examples of the 5-E approach in schools are described elsewhere (Murphy, 1997; Murphy & Duncan, 1997).

Conclusion

There is an oft-told story about a man who was walking down the street when he spotted his friend searching for something under the streetlamp. When the man asked what he was doing, his friend explained that he was looking for his lost keys. The man joined his friend in the search, and they continued looking for several minutes without success. Finally, he asked his friend where he dropped the keys. “Way over there,” his friend replied, pointing to a field across the road. “Then why, might I ask, are you looking here?” Without hesitation, his friend stated, “Because the light is so much better here than over there.”

Practitioners have traditionally searched for the keys of change on the familiar road of client deficiencies and weaknesses. Research on common factors suggests that solutions are more plentiful on the less familiar road of strengths and resources. The empowerment of client resources and hope within a collaborative framework is the central theme of the 5-E process and of empirical findings regarding change in psychotherapy and schools. This chapter invites practitioners to “do what works” instead of merely doing what is familiar. Finding the keys is always more important than looking under the light.

Adapted from:

Murphy, J. J. (1994). Working with what works: A solution-focused approach to school

behavior problems. The School Counselor, 42, 59-65.

Murphy, J. J. (1999). Common factors of school-based change. M.A. Hubble, S. D., Miller, B. L. Duncan (Eds.), The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy. Washington,DC: American Psychological Association. (pp. 361-386).